“But the personality of the site—and something of the winemaker, too—comes through no matter what.”

—Chris Howell

“The flowering of Spring Mountain,” Wine News, June 2007:

It’s a glorious April morning high on Spring Mountain and the sun has a new, welcome warmth to it. A pileated woodpecker calls from the oak forest that surrounds Cain Vineyard & Winery. Perched in the Mayacamas Mountain range that rises to the west of the flat Napa Valley floor, the cobblestone winery commands a view 25 miles westward, clear across Sonoma County to the edge of the Pacific. The cool maritime fog that gathers over its cold waters each night rolls inland before dawn and laps over Spring Mountain’s foothills.

But it never reaches the higher elevations, which become islands in the sea of fog. This daily ebb and flow has profound effects on the mountain fruit grown here, especially the Cabernet Sauvignons and Meritage blends that show graceful, rather than gritty, tannins, pure and silky fruit flavors, lip-smacking acidity and, rare in California reds, a distinct core of welcome minerality.

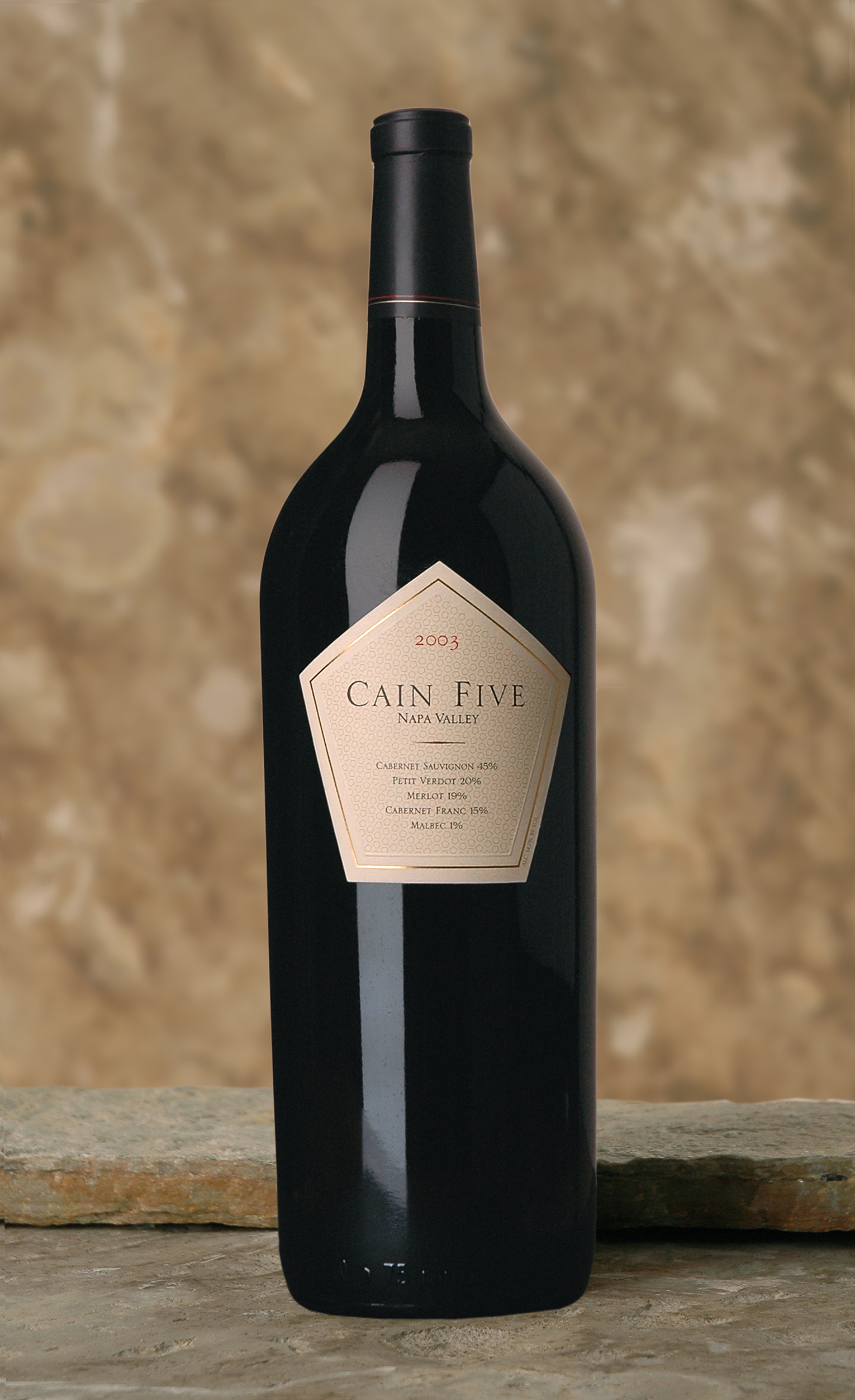

I have made a pilgrimage here because a bottle of 1990 Cain Five made from Spring Mountain fruit remains the single-most delicious California Meritage I’ve ever tasted. In the 14 years since I acquired that bottle, the number of wineries on Spring Mountain has blossomed from a handful to nearly three dozen. At a tasting in February 2006 that featured most of them, I found the overall quality of the wines to be extraordinary. I couldn’t help but wonder what it was about Spring Mountain, named for the many springs that feed small streams in this upland area, that produces such gorgeous fruit.

The answer, like the wines, is complex. Cain winemaker and general manager Chris Howell explains, “Spring Mountain isn’t a single coherent thing. It starts at 400 feet above sea level down near the valley floor and rises to 2,600 feet and above. The uppermost of our vineyards here at Cain are at 2,100 feet and the lowest are at 1,400.” He shares a satellite photo of the whole appellation that depicts vineyards as scattered patches that form a rough “V” pointing from east to west. Below the “V” to the south are Cain’s vineyards, apart from the rest.

Although Howell notes that “there’s no uniform altitude, exposure or soil type,” he does identify some unifying elements: “We’re all on the lee side of the Napa Valley, up in the Mayacamas range. Most of the slopes face east, so we get morning sun. And we get Pacific weather—storms drop more rain here than across the valley in the Vaca Mountains.”

Spring Mountain rises at mid-valley west of St. Helena between Mount Veeder to the south and Diamond Mountain to the north; each of the three has earned AVA status (Spring Mountain in 1993) and each is lusher, greener and more heavily forested than the dry, hard-scrabble Vaca Mountains that define the eastern side of the valley. As storms move over the Mayacamas range, they drop a lot of their rain, leaving less water for the Vaca range.

As Howell notes, soils differ on Spring Mountain (the AVA encompasses about 8,600 acres with 1,000 planted in red grapes and 100 in white), depending on location. “The underlying material here at Cain is what’s called Franciscan shale,” he says, referring to the austere, infertile mountain soils formed from sedimentary rock—once ocean bottom—that’s exposed up in the mountains.

Other areas of Spring Mountain (and nearby Diamond Mountain, too) have primarily volcanic soils formed from the volcanoes that erupted here five million years ago. (Even today, molten lava rolls beneath the surface as evidenced by the geyser and hot springs that have made the town of Calistoga, capping the north end of the valley, rather famous.)

“I’m starting to get a sense of this place after 16 years here,” Howell allows. “I see that great wine regions are an outgrowth of interactions between cultures and sites. Our vineyards are idiosyncratic. The soil is poor and the vines hard to grow. But the personality of the site—and something of the winemaker, too—comes through no matter what.”

In 1996, Howell was forced to replant due to the phylloxera outbreak that swept through northern California vineyards and weakened the vines. “I was worried that I would mess things up, that changing the rootstocks and the budwood would reduce the quality of the wines. But…the site ultimately tied it all together.”

Cain Five, like the bottling that drew me here, is composed of the five Bordeaux varieties—cabernet sauvignon, merlot, cabernet franc, Malbec and petit verdot. But the amounts shift, Howell notes, “depending on what nature gives us. And I’m picking the fruit riper now. The wines used to be about 13.5 percent alcohol, and now they’re 14 to 14.5. I’m doing shorter maceration times—just 10 to 14 days. The wines undergo full malolactic in the barrel. And because this is mountain fruit, I have to carefully manage the tannins.”

By Jeff Cox