“What do we like in wine? When the phenolics are ripe, is there anything left?”

—Chris Howell

“Cain Five and the Question of Ripeness,” Aspen Daily News, December 2012:

More this week on the nuances of terroir and the modern culture of winemaking, as we consider the wines we make and the wines we like to drink.

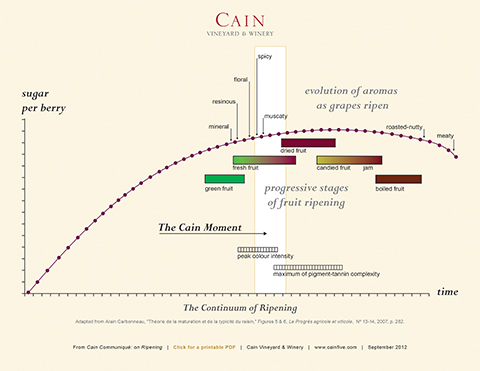

Our point of reference is a chart mapping and graphing the continuum of grape ripening, developed by Alain Carbonneau. Here we consider the juice versus skins in the context of the “arc of ripening.”

The arc employs a fruit color and flavor spectrum similar to those old wine tasting flavor wheels. Carbonneaus’ model makes sugar levels the vertical axis, while the horizontal represents the temporal continuum. He places peak color intensity and maximum pigment-tannin complexity to the points on the arc, noting progressive stages of fruit ripening, along with the evolution of aromas as those grapes ripen. For example, early ripening would give mineral notes and “green” flavors like green bean or vegetal. On the far right end of the spectrum, candied, jammy and boiled fruit flavors lose the previous aromas and offer roasted, nutty, meaty aromas.

This chart has been developed with the specificity of every vineyard the world over in mind. Each vineyard, every row — even vines within a row — have their own “sense of place” in terms of vigor and speed of ripening. There would be a unique chart for each vineyard, variety and even each vintage.

Furthermore, the synchrony of ripening of separate grape attributes must necessarily be unique to each vineyard —just like a fingerprint, no two are the same — so aromas ripen at a different rate relative to tannins and color. More importantly, there is no such place as “ripe” —it is always a matter of degree —as in more ripe or less ripe.

In other words, this chart is merely a schematic for thinking about the unique phenomena of ripening, but it helps give a deeper look into regional or even single vineyard distinction. Seldom are two rows alike. Here lies the “Cain Moment,” as a white box overlies the points on the arc, with corresponding aroma, color and tannin levels. Every winery has their moment. For Chris Howell, general manager/winemaker at Cain Vineyard and Winery in St. Helena, Napa Valley, Calif., it is on the softer, quieter side. Green, fresh and dried fruits with aromas of floral and spice, and barely a quarter of the way along the pigment/tannin scale.

Intentional and opinionated, Chris is not shy about standing against the norm in a tightly knit place like Napa, whose styles border on the hedonistic. He asks me a series of questions about phenolics and wine: “What do we like in wine? When the phenolics are ripe, is there anything left?” Some of these questions are more straightforward; some more easily answered than others. Chris and I think (and drink) a lot alike. Some color is good; too much is not so good. We like delicacy and finesse, wines with preserved floral characteristics. Neither of us care all that much for the almighty power of ripeness. Texture interests Chris, so his wines will invariably soften as they ripen, which we will soon discover, since he just opened a 1999 Cain Five, which he calls a psychologically challenging vintage following the glory of ’97 and a good ’98.

A winemaker’s experience of his or her domain is only one issue; but again, primary to a wine’s path through the vinification process and into (hopefully) a long, aged life, is the choice to pick at a moment when the terroir is singing clearly. Chris uses the word “process” to describe modern winemaking because his experiences of vintages ago — in France as a winegrower (vigneron) and in Napa —were more about guiding eventual outcomes.

But this experience of terroir should not be the only issue. We agree that pleasure in the glass might be our ultimate goal, only as winemakers we may not all agree on what that is. In the case of wine, like art or music, pleasure is not the same for everyone. Just as some folks may prefer Velveeta smoothness, some may prefer fat, “overstuffed” wines. Others still may prefer wines that hold their attention, refresh their palates, awaken their imaginations, and have something to say. It is for this last set that Chris has dedicated more than 20 years working toward at Cain. His concern lies with connecting to the unconscious through sensuality, and it lives in the realm of one word: B-a-l-a-n-c-e.

This is the domain Chris and I share, as we sip on a 2010 Stony Hill Napa white riesling and the ‘99 Cain Five whilst trying to eat wood-oven roasted Brussels sprouts with aged balsamic and Parmesan; black truffle pizza and crisped duck over apple and Asiago risotto. The light and linear white riesling (lacking the usual loads of terpene-inspired flavors) effortlessly marries every flavor on the table, as one would expect. More surprising is how the Cain Five, made of the five Bordeaux varietals, confirms and upholds this marriage. It naturally flows with the cheese flavors; elevates the truffles, dazzles with the duck and brings out an earthy, nuttiness in the Brussels sprouts while paying homage to the surly vegetalé of it all.

Does your big red do that? Cheers! Remember, wine reveals truth.

By Drew Stofflet, who lives in Carbondale. Correspond with him at [email protected].